With over $70bn in sales generated from products developed from the work of academic scientists at just 200 US institutions (AUTM figures), it’s no surprise that companies are increasingly turning to academia to access these leading scientific and engineering minds for their R&D efforts. Partnering with universities can help companies cut costs and accelerate internal R&D, bringing exciting new products to market faster.

When these strategic partnerships go well, they combine the innovation-driven environment of the corporation with the discovery-driven culture of the university. Academic scientists are clever people with enormous knowledge in their chosen areas of specialization and they frequently come up with exciting new technologies.

In this report, we’ll show you how to identify the science and the scientists who would be most relevant to your company and its products.

Let us begin by differentiating between the different sorts of outputs that come from academies and their value to a tech scout.

Research Papers

Research papers are the core output of an academic’s work and it is on this basis that researchers are evaluated by their peers, those who fund their work, the institutions that employ them and – pretty much always – how they evaluate themselves.

Think it through, from their point of view: you have spent years working on an area of science to get to the point where you are undisputed expert worthy of government funding, space in a lab, tenure at a university or similar. What you want to do now more than anything is prove to everyone that you are worth it all. Come up with something novel and interesting (possibly even exciting), then prove to the funding bodies and your peers that you did so.

The route to success is therefore to publish ideas that everyone can read. Evidence of useful experiments, that is the goal, and the higher the profile of the journal, the better. And, just to be fair, many academic scientists also thoroughly enjoy their science, so it is an end itself and not just a mercenary objective.

Since these scientists are playing to this field, their peers and funders, most research – while undoubtedly of academic interest – is of limited interest to the wider world. Think of a gymnast. The straddle planche on the rings is unbelievably hard and if you can do one, other gymnasts and the judges at the competition you are will be deeply impressed – if the competition is the Olympics then this is an extraordinary achievement. However, for all the strength and flexibility implied by this talent, opportunities to perform the straddle planchet on rings in your local pub are going to be few and far between. Most academic research is going to be a bit like that: mental athletics of the highest calibre, difficult to apply immediately in non-academic settings.

So, if someone comes along, half-way through that process and offers an academic a share in unproven revenues to stop working on the research idea and instead start turning it into a product that the businessperson may be able to sell, chances are that this will not create great interest.

The problem for you, as a commercially minded person, is that if you wait and they publish the idea or experiments’ results, these are then in the public domain, so you cannot patent them to protect the IP going forward. Many academic scientists will not be willing to wait the (give or take) 2 years it takes to secure the patent, before publishing. So, even if they are open to helping you to develop their idea beyond the lab to a prototype or equivalent stage, the limitation on publishing will be a big issue for them.

But if waiting is viable for you, then you should still remember what it means when a program of academic the work is finished. Academics do not want to wake up to find themselves on the street because all their funding has dried up. So towards the end of one program of work, most likely they will have a new idea already set up to work on, with funding applications out for review, post-docs being hired and PhD students recruited. So, the old idea that you want to focus on is yesterday’s work and it is likely that the researcher will not want to work on the idea for you.

These factors add up. Some (from a commercial point of view) disappointing research was actually done on this by HEFCE, the public funding body in the UK. They found that 90% of academic researchers did not want to work with an industrial partner, even if one was found who wanted to work with them. HEFCE also asked the tech transfer offices of the universities to comment on this and the feedback was that, because of the significant difference in approaches (speed and responsiveness being the biggest issues), 80% of the academics who were willing to work with industrial partners, were sooner or later dropped by the partner anyway. In other words, 98% of the academics were not really going to be of any use to an industrial partner.

Putting all these factors together means that reviewing scientific literature is valuable but there is an enormous amount of material to shift through, to get to the material you as a business need. And a lot of time can be wasted approaching academics who will never want to work with you.

However, if you have a strong R&D department, then reviewing purely academic research may still provide excellent ideas from which products can be developed, with your company filing its own patents on the extension of the idea of form of the implementation involved in your company’s work. Or the idea may be sufficiently niche, that other companies are unlikely to be able to do much with it, so in effect you have a clear run at the NPD in any case.

TTOs

However, most universities and other research institutions (RIs) have technology transfer offices (TTOs). These are staffed with people whose job it is to identify the most likely commercially applicable science from the researchers in the university and to convince them that they should be willing to discuss their work with potential industrial partners, in order to attract revenues for the university and possible further (corporate) funding for the researchers themselves. We at Innovation DB call this their ‘offers’, as they are promoting them to industry, but there is no common name for the material produced.

What you will get here is a tiny subset of the research going on, but the problems given above will mostly have been solved. This includes the issue of patenting, as the TTO will, in most cases, have started the process of acquiring a patent, even if it is still pending. You can simply acquire or license the patent from the university.

You may, of course, have a slightly different view of the way the patent should be filed – especially if you already have a patent portfolio into which this new patent would fit – so patent problems do not disappear, but it is a good start.

Also, there are projects, about which information is published, which can give strong clues as to both the areas of science that can be applied commercially and the scientists who are willing to collaborate with industrial partners. Looking at grants and awards offered to research institutions in combination with commercial partners is an excellent source of this sort of information. The TTOs will also promote information on collaborations (where they are not kept strictly private because of commercial sensitivities).

There are also patents themselves, of course. Universities and RIs – as a general rule – do not incur the expense of filing patents unless they see a commercial potential. Patents, of course, are written to protect IP and do not always do a good job of describing how to apply a novel technology, but they are still a great source of information. Filing a patent takes time, so the ideas to be found there will lag behind the ‘offer’ data and, unfortunately, universities often file in multiple versions of their own name, sometimes even misspelling their own name on the patent (extraordinary but true), which makes searching for data a pain.

Finally, and by no means least, there are many excellent conferences with partnering opportunities, where academics themselves, or their TTOS, will come expressly to promote their work or specific technologies, and meeting at these events can be invaluable. However, conferences cost a lot of time and money, especially once travel and accommodation is included.

For large companies, having a dedicated team that visits conferences is definitely worthwhile, allowing proper conversations and evaluation of ideas, but still much less efficient than searching by other means. The optimum, if you have the budget, is to do both. If you do not, however, then huge amounts can be learned by researching the data alone.

So, where to start?

The first step to unlocking the market value of the world-class science that academic scientists produce, is to be able to quickly identify the science and the scientists who would be relevant to your company and its products.

That is why, with active support from our clients, such as PepsiCo, Lilly, Philips, Magna, GSK, Beiersdorf and others, we built a database of commercially interesting technology from around 5,000 academic institutions across 200 countries, all over the world, to make it dramatically easier to identify technologies of interest.

Innovation DB gives you all the top universities across the globe, not just MIT or CalTech, but Cambridge, Oxford, Tsinghua and Singapore, Zurich and Paris, and thousands of others.

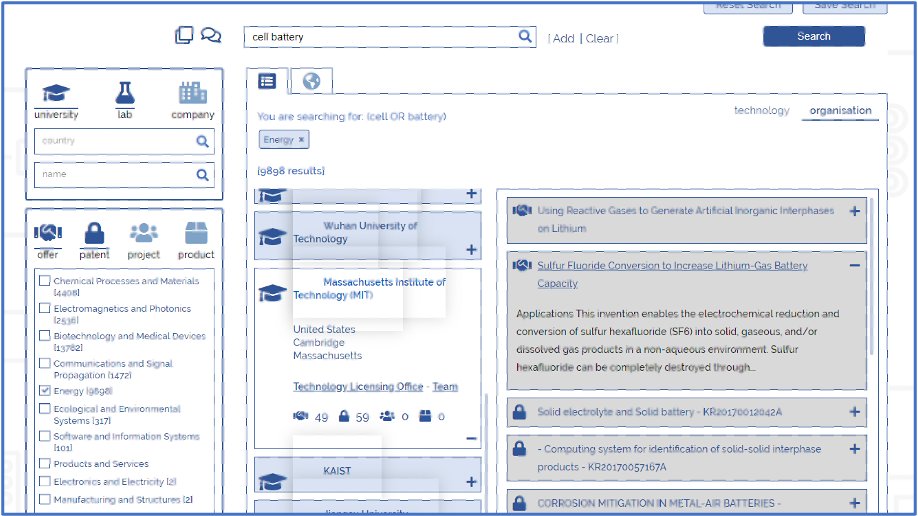

First search for something of interest:

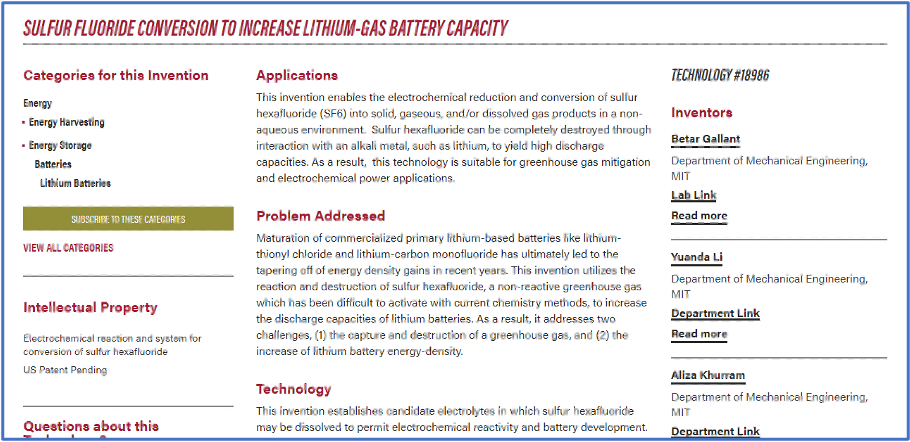

Then drill into technologies of interest, to see more details and who came up with the tech:

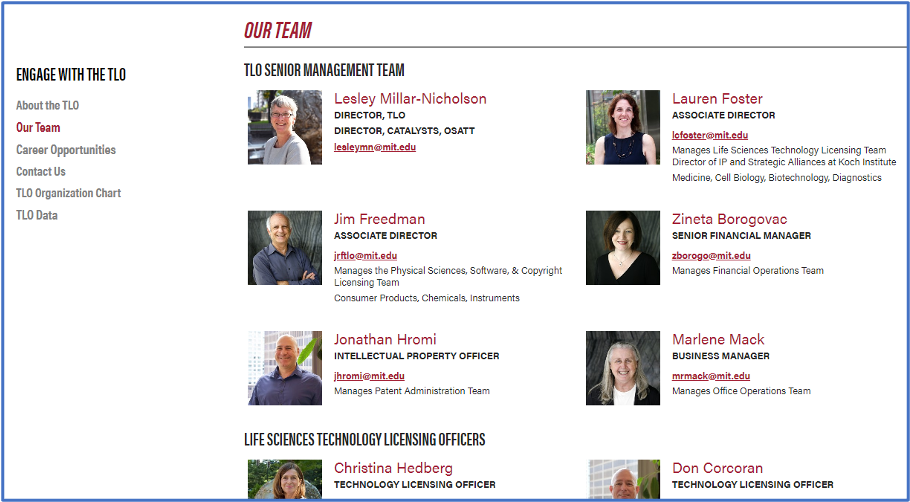

Then check out the details of the university’s representatives who can help you:

Of course, there are excellent patent databases out there and it is possible to visit the sites of universities directly and find material there. Or you could also just search the web. Our testing of this, with our customers, has shown massive time savings (one test, with a pharma client, found 13 in the first search of our database out of the 16 items that the company’s own researcher had found in two days of searching the web) and also greater thoroughness (a comparison test with another client found that in about 10 minutes on our database, the client discovered 5 new items of interest to add to the results of a project he had conducted over 6 weeks).

If you are curious, of course we welcome the chance to show you what we have built.

Conclusion

There is excellent material to be found in universities and RIs that can help NPD at your company.

✅ Academic research per se will have much of value, but will take enormous sifting.

✅ TTOs will et you to the useful material much more quickly and are very helpful in supporting companies interested in working with their scientists.

✅ Conferences are excellent sources of material also, if you have the time and budget for them in the mix.

✅ Finally, patent databases will provide large amounts of relevant data, but the ideas found there will be older than those from TTOs and you may need help working out the value of the patent to your company, so you will likely want to talk to the relevant TTO in any case.

Written by Dr Gerald Law, CEO of Innovation DB www.innovationdb.com

Innovation DB provides a global database of academic technologies with commercial potential, currently listing over 600,000 technologies, from about 5,000 institutions and universities, in more than 200 countries.

We are the trusted partner of blue-chip multinationals from many sectors, but also Venture Capitalists, mid-size and small R&D intensive companies and technology consulting firms.